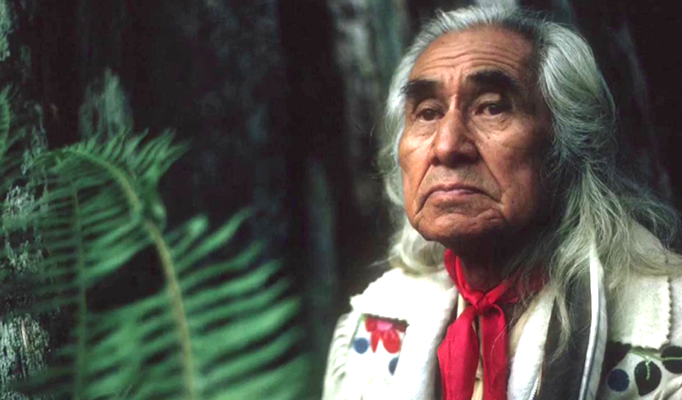

Like Chief Joseph Brant, Chief Dan George has left a remarkable Canadian legacy. He himself was a chief’s son. In the 1990 North Vancouver Centennial book, Chuck Davis describes Chief Dan George as one of North Vancouver’s most famous citizens. Born on July 24, 1899, Chief Dan George died at age 82 on September 12, 1981. His birth name was Gwesanouth/Teswahno Slahoot, meaning ‘thunder coming up over the land from the water’. His name was changed to Dan George when he entered the Native residential school at age 5. He memorably said that “A man who cannot be moved by a child’s sorrow will only be remembered with scorn.” Sadly, the use of his indigenous language was forbidden. “My culture”, said Chief George, “is like a wounded stag that has crawled away into the forest to bleed and die alone. The only thing that can truly help us is genuine love.”

Children, Grand Children and Great Grand Children

We had the privilege of attending the fifth Annual Tsleil-Watuth Nation Cultural Arts Festival held at Cates Park/Whey-ah-Wichen. The festival celebrated the 30-year legacy of Chief Dan George. While there, we attended the Legacy tent. The Legacy Tent leader, Cheyenne Hood said: “…My mother is Deborah George, who is the daughter of Robert George, who is the son of Chief Dan George. He is my Great-Grandfather. A lot of people while I was growing up used to ask me what it was like to have Chief Dan George as your Great-Grandfather. To be honest, I never really knew of his fame, the things that he had done, because I was a fairly young child. To me, he was always just Grandpa Dan, or Papa Dan. I didn’t know that he was a movie star. I didn’t know that he went to Hollywood. I didn’t know that he was a writer or a poet. He was just a grandfather.”

“‘My best memory of him’, said Cheyenne, “is after his wife died. He used to take turns with different children and spending time in their homes. His daughter Rosemary used to have an old house that had a steep set of stairs. It faced the Burrard inlet. They had a swing in the backyard. We were over visiting my grandparents and we went trucking over there to see who was at the swing, to see who I could play with for the day. I saw Grandpa Dan sitting on the porch, facing the water. He had his face up to the sun, and he kind of reminded me of a turtle on the rock.”

“My curiosity got the better of me, so I walked up the stairs and said: “Grandpa, what are you doing?’ He took a few minutes to answer me and said: ‘I am sitting’. He said: ‘Do you want to come sit with me?’ So, I climbed to the top of the stairs, and sat down there beside his feet. He was sitting there with his face to the sun. I said: “Grandpa, what are you doing?” He said: ‘Do you feel that?’ And he leaned his head back and he had his eyes closed. I kept looking at him: ‘What is he doing?’ So, I mimicked him, copied him and closed my eyes with my face to the sun. He said: ‘Do you feel that?’ After a few minutes, I said: ‘Yes, I do.” He said: “What is that?” I said: ‘That is the sun on my face.’ Then he started to talk about the importance of the sun and what it does for mother earth, and what it does for nature, and nature’s cycles. I sat there feeling the warmth of the sun spread across my face.”

“Grandpa Dan said: ‘Do you hear that?’ So, I listened quietly. I said: ‘Yes, I do.’ I said: ‘What is that?’ He said: ‘That is the wind blowing through the trees.’ Grandpa smiled, a really faint kind of smile. Then he started talking about the importance of the wind and the role that it plays with the trees and the music that it makes.”

“Then he said: ‘Do you smell that?’ I am still sitting there with my eyes closed. I said: ‘Yes, I do.’ He said: ‘What do you smell?’ I said: ‘I smell the salt from the inlet.’ Then he started talking about the role that the water and the inlet played for our people and our nation, and how when the tide went out, we were able to go out and feast and eat. We had clams and mussels and crabs and we could fish, and we could harvest sea food. He said: ‘Do you hear that?’ I sat for another few minutes listening, and then I said: ‘Yes, I can hear that.’ He said: ‘What do you hear?’ I said: ‘I hear the waves crashing against the rocks.’ Then he started talking about the history of the Tsleil-Watuth Nation people, and how we came to be, and how we moved through this life and this world. I sat and I listened, and we were quiet for a few minutes, and then I opened up my eyes. He was looking down at me and he was smiling. I said: ‘What are we listening for now, Grandpa?’ He said: ‘Nothing’. I said: ‘What are you going to do now, Grandpa?’ I just wanted to be near him, I just wanted to be with him. He said: ‘Now we are going to go inside and have tea and bannocks’. And we did.”

Dignified elder

Chief Dan George once said: “I would be a sad man if it were not for the hope I see in my grandchild’s eyes.” Chuck Davis commented that Chief Dan George “embodied the dignified elder.” As one of eleven children, he became a longshoreman, working on the waterfront for twenty-seven years until he smashed his leg in a car accident aboard a lumber scow. Chief Dan George also worked as a logger, construction worker, and school bus driver. He formed a small dance band, playing in rodeos and legion halls. His instrument was the double-bass.

In the original Deep Cove Heritage book, Echoes Across the Inlet, it speaks about how Chief Dan George gave his historic Centennial ‘Lament for Confederation’ address in 1967 to 30,000 people at the Empire Stadium in Vancouver. Memorably he commented: “I shall see our young braves and our chiefs sitting in the houses of law and government, ruling and being ruled by the knowledge and freedoms of our great land. So shall we shatter the barriers of our isolation. So shall the next hundred years be the greatest in the proud history of our tribes and nations.”

Residential school

Sent to residential school at age 5, Chief Dan George never lived to see the day when Prime Minister Stephen Harper and the Government of Canada apologized to the First Nations people for the trauma many experienced in the Residential Schools.

Acting career

He first acted in the 1968 TV Series Cariboo Road which became the movie Smith. He went on to win the 1970 Oscar for Best Supporting Actor in the hit movie Little Big Man. Chief Dan George made famous the phrase: “It is a good day to die.” Dustin Hoffman commented “I was amazed at his energy (he was in his seventies); he was always prepared with his lines; it was a six-day week; we were shooting thirteen hours a day.” Helmut Hirnschall noted that “His quiet assertion, his whispered voice, his cascading white hair, his furrowed face with the gentle smile became a trademark for celluloid success.”

From there, he went on to act in many films and TV shows, including The Outlaw Josey Wales, Harry and Tonto, and the TV series Centennial.

Honours

Many honours have been given to Chief Dan George including being made an Officer of the Order on Canada in 1971. In 2008 Canada Post issued a postage stamp in its “Canadians in Hollywood” series featuring George. An Abbotsford public school and a Victoria theatre have been named after him. In the opening ceremonies of the Vancouver Olympic Games, his poem “My Heart Soars” was quoted by Actor Donald Sutherland. To us, Chief Dan George, with his pithy sayings, was a Benjamin Franklin of the indigenous world: “The beauty of the trees, the softness of the air, the fragrance of the grass, they speak to me…”

Faith

His poetry and prayers are gripping and unforgettable. As Chief Dan George said; “…I am small and weak. I need your wisdom. May I walk in beauty. Make my eyes ever behold the red and purple sunset. Make my hands respect the things that you have made, and my ears sharp to hear your voice. Make me wise so that I may know the things that you have taught your children, the lessons you have hidden in every leaf and rock. Make me strong not to be superior to my brothers but to fight my greatest enemy –myself. Make me ever ready to come with you with straight eyes so that when life fades as with the fading sunset, my spirit will come to you without shame.”

In getting to know his son Robert/Bob George, we gained a glimpse of the deep spirituality and humanity of his father. His son Bob George had us over to his house where we watched the Alpha Course and prayed many times together. He said, “Everyone in our Tsleil-Watuth nation needs to watch these Alpha videos.”

May Chief Dan George’s legacy continue to inspire many to seek truth and reconciliation as Canadians.

Leave a Reply