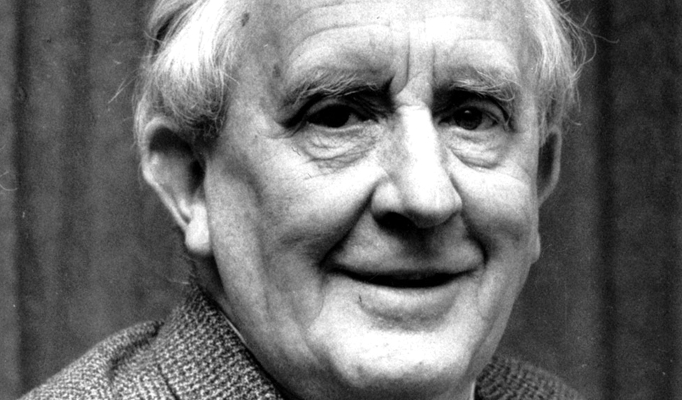

Can writers actually set the world on fire? What caused the late J.R.R. Tolkien to be a literary superstar who continues to captivate generation after generation of new readers? Amazon is reportedly spending a billion dollars in their upcoming prequel Lord of the Rings TV series, focusing on the second age of Middle Earth, the time when the Rings of Power were forged.

Unlike his good friend, C.S. Lewis, he was a most reluctant celebrity who would rather be left alone, or be with one good friend. Without Tolkien leading C.S. Lewis to Christ, there would have been no Chronicles of Narnia. Without Lewis’ encouragement, The Lord of the Rings would have likely never been published. Literary iron sharpened iron.

Tolkien was born in Bloemfontein, South Africa, January 3, 1892. Bitten by a tarantula at age three, he left South Africa with his mother, Mabel, and younger brother, to live in Britain. His father, Arthur, stayed behind working at the Bank of South Africa, before dying a year later from rheumatic fever.

For four years, Tolkien lived in the hamlet of Sarehole, outside of Birmingham, in the English midlands. The deep love of nature expressed in his books goes back to this period. “I am at home,” said Tolkien, “among trees.” He called it, “four years, but the longest-seeming and most formative part of my life.” Though he liked to draw trees, he liked most to be with trees. He would scramble up them and even converse with them. It disappointed him that not everyone shared his feelings towards them. Cutting trees for no good reason deeply upset him. During the siege of Isengard and Battle at Helm’s Deep in the Lord of the Rings, it is the wanton cutting of trees by Saruman that causes Fangorn to influence his fellow Ents, and the scarier Huorns, to become involved. Tolkien later commented, “I am in fact a hobbit in all but size. I like gardens, trees, and unmechanized farmlands; I smoke a pipe and like good plain food (unrefrigerated)…I do not travel much.”

When they moved to Birmingham in 1900, with its pollution and smell, Tolkien felt trapped. His resilient mother instructed him in Latin, German, French, and the basics of linguistics, awakening in him a lifelong passion for languages, alphabets, and etymologies. In a letter to his son Michael, he remembered his mom as a ‘gifted lady of great beauty and wit, greatly stricken by God with grief and suffering, who died in youth (at 34) of a disease (diabetes) hastened by persecution of her faith.’ Mabel’s father, John Suffield, who had become a Unitarian, was deeply upset by his daughter’s strong Christian faith, cutting her off financially. Traits of his mother appeared in his books, as the quintessential suffering, sacrificial woman.

Humphrey Carpenter, a Tolkien scholar, said that after the death of his mother in 1904, Tolkien became ‘two people’: one ‘cheerful, almost irrepressible’, the other ‘capable of bouts of profound despair’. Does that remind anyone of Frodo? Fr. Francis Morgan, who smoked a large cherrywood pipe that would have been the envy of any hobbit, became his legal guardian. After being threatened with severe consequences by his guardian, Tolkien was forced to break up with his future wife, Edith, until he turned age 21. Tolkien’s first year at Oxford, after losing his girlfriend, was very unfocused. He did little homework, stayed up late, and rarely attended church. His literary breakthrough happened when he discovered Finnish grammar, saying, “It was like discovering a wine-cellar filled with bottles of amazing wine of a kind and flavour never tasted before. It quite intoxicated me.” This became the portal to his creation of new Nordic languages, resulting in the secondary world of middle-earth.

C.S. Lewis said that because Tolkien was a linguistic inventor, this “was undoubtedly the source of that unparalleled richness and concreteness which later distinguished him from all other philologists (study of literary texts and words). He had been inside language.” Tolkien made the often-dry subject of philology come alive. Carpenter commented that “certainly there had been no one before him who brought such humanity, one might say such emotion, to the subject.”

Shortly after marrying Edith, Tolkien was shipped off to the WWI trenches in France. He was deeply impressed with the ordinary British soldiers, with their humour, toughness, and ability to endure any kind of adversity. Tolkien commented, “My Sam Gamgee is indeed a reflection of the English soldier, of the privates…I knew in the 1914 war, and recognized as so far superior to me.” At the end of 1915, Tolkien contracted trench fever, a highly contagious disease spread by lice which thrive in the filth of the trenches. He commented later, “by 1918, all but one of my close friends were dead.”

Tolkien was the Oxford professor of Anglo-Saxon from 1925 until 1959. Even though his rapid mumbling speech made it hard for the students to always hear him, they loved how he invariably brought the subject alive and showed how much it mattered to him. Being a perfectionist, Tolkien worked on The Lord of the Rings for 18 years before it was being published in 1955. C.S. Lewis described Tolkien as ‘that great but dilatory and unmethodical man.’

Philip and Carol Zalenski, key Tolkien scholars, held that the Lord of the Rings trilogy “possess an intrinsic grandeur, breadth, and profound originality – it is simply the case that nothing like this has ever been done before – that makes them landmarks in the history of English literature.” Tolkien commented that “The Lord of the Rings is of course a fundamentally religious and Catholic work; unconsciously so at first, but consciously in the revision. That is why I have not put in, or have cut out, practically all references to anything like ‘religion’, to cults or practices, in the imaginary world. For the religious element is absorbed into the story and the symbolism.”

At its most profound level, The Lord of the Rings is a Good Friday passion play. The carrying of the ring which is the emblem of sin, is the carrying of the cross. This is the applicability of the Lord of the Rings that we have to lose our life in order to gain it; that unless we die, we cannot live. Tolkien wrote, regarding the final climactic moments on Mount Doom, “I should say that within the mode of the story, [it] exemplifies [an aspect of] the familiar words: ‘Forgive us our trespasses as we forgive them that trespass against us. Lead us not into temptation but deliver us from evil.’” The doom/fate of Middle Earth holds true for the same cosmic reason that the Passion of Christ is necessary to break the Fall and Mortality. Is it a mere coincidence that Tolkien had both the Ring and the Dark Lord destroyed on March 25, the traditional Anglo-Saxon date for Jesus’ crucifixion? In a nonallegorical sense, the forgiveness of the cross was at the centre of the Lord of the Rings.

What if we too would be willing to forgive, to die that we might live? What if we, like Tolkien, could use language to bless and not to destroy, to set the world on fire with love?

Leave a Reply