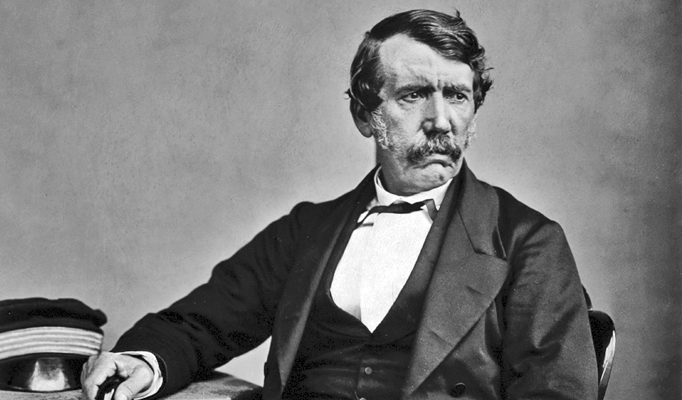

Dr. David Livingstone originally trained as a missionary doctor to China. When that door closed because of the opium wars, Livingstone ended up in Cape Town, South Africa. Having received the Royal Geographic Society’s highest golden medal, Livingstone lived in an era where no occupation was more admired than that of an African explorer. Sir Roger Murchison, President of the Royal Geographical Society, at Livingstone’s Westminster Abbey funeral, called it “the greatest triumph in Geographical research that has been affected in our times.”

Martin Dugard (author of Into Africa, Stanley & Livingstone) holds that Livingstone was a man whose legend was arguably greater than any living explorer. In the backdrop of the Crimean War, England was ripe for a hero, someone to cheer for. Dugard comments, “Livingstone reminded Victorian Britain about her potential for greatness. The fifty-one-year-old Scot was their hero archetype, an explorer brave, pious, and humble; so quick with the gun that Waterloo hero, the Duke of Wellington, nicknamed Livingstone ‘the fighting pastor’.”

Livingstone had the mystique of a modern-day astronaut boldly going into unchartered territory. Travelling, said Livingstone, made one more self-reliant and confident. He only wanted companions who would go where there were no roads. His books were bestsellers and his lectures standing room only. Crowds mobbed him in the streets and even in church. One poll showed that only Queen Victoria was more popular than the beloved Livingstone.

Many chiefs heard through Livingstone for the very first time of the Father’s amazing love: “Surely the oft-told tale of the goodness and love of our Heavenly Father, in giving up His own Son to death for us sinners, will, by the power of His Holy Spirit, beget love in some of these hearts.” Livingstone noted: “Baba a mighty hunter and interpreter sat listening to the Gospel in the church at Kuruman, and the gracious words of Christ, made to touch his heart, evidently by the Holy Spirit, melted him to tears; I have seen him, and others, sink down to the ground weeping.” Chief Sechele of the Bakuena tribe, upon hearing the gospel for the first time, said “You startle me – these words make all my bones to shake – I have no more strength in me, but my forefathers were living at the same time yours were, and how is it that they did not send them word about these terrible things sooner? They all passed into darkness without knowing whither they were going.”

Eager that his tribal followers would also become followers of Jesus, Chief Sechele had to be talked out of forcing them to believe in Christ: “Do you imagine that these people will ever believe by your merely talking to them? I can make them do nothing except by thrashing them; and if you like, I shall call my head men, and with our litupa (whips of rhinoceros-hide), we will soon make them all believe together.” One chief Sekelutu was drawn to Livingstone, but afraid to read the bible in case it might change his heart and make him content with just one wife. Livingstone knew that the Bible changes everything, calling it “the Magna Carta of all the rights and privileges of modern civilization.”

Livingstone literally filled in the map of Africa, exploring all of its main rivers, covering 29,000 miles, greater than the circumference of the earth. One of his most famous discoveries was the Victoria Falls, named after Queen Victoria, on the Zambezi river: “It had never been seen before by European eyes, but scenes so lovely must have been gazed upon by angels in their flight.” During his extensive travels, he suffered over twenty-seven times from attacks of malaria, being reduced at one point to ‘a mere skeleton’. His wife Mary tragically died from malaria in 1862 while traveling with her husband in Mozambique. Livingstone wrote in his Journal: “I loved her when I married her, and the longer I lived with her I loved her the more. A good wife, and a good, brave, kind-hearted mother was she. God pity the poor children, who were all tenderly attached to her; and I am left alone in the world by one whom I felt to be a part of myself.”

Livingstone had been lost for five years in Africa and presumed dead by many. Welsh born, American journalist Morton Stanley, originally named John Rowlands, was sent by the New York Herald in 1871 to Africa to rescue Livingstone. Two Hundred and Thirty-Six days later, after a seemingly hopeless search, Stanley found him, uttering the immortal words “Dr Livingstone, I Presume.” His discovery was voted the greatest 19th century newspaper story. Stanley called Livingstone “…an embodiment of warm good fellowship, of everything that is noble and right, of sound common sense, of everything practical and right/minded…” Speaking to the 57 men carrying supplies to Livingstone, Stanley said: “He is a good man and has a kind heart. He is different from me; he will not beat you as I have done.” After returning to England, Stanley was initially rejected by the London Geographical Society as an imposter, until a letter was suddenly received just as Stanley walked out. In the meantime (three months after Livingstone had been found), Florence Nightingale led a fundraising drive raising four thousand pounds to rescue Livingstone, with a team that included Livingstone’s twenty-year-old son Oswell. “If it costs ten thousand pounds to send him a pair of boots, we should send it. England too often provides great men then leaves them to perish.” Queen Victoria went out of her way to thank Stanley for discovering Livingstone, said that she had been very anxious about his safety.

Livingstone called the slave trade the open sore of the world, believing that opening up trade routes would eliminate the slave trade. Dugard noted that “…slavery became the cornerstone of Portugal’s economy.” Hundreds of thousands of Africans were exported by Portugal from both the east and west coast. Dugard commented that “Livingstone’s antislavery speeches, it seemed, were offending Prince Albert, Queen Victoria’s husband. Albert’s cousin Pedro also happened to be King of Portugal.” His on-location report of 400 slaves massacred by slave traders at Nyangwe was key in ending the slave trade. He mistakenly thought that discovering the source of the Nile would open up trade routes for Africans, ending their dependence on the slave trade. Livingstone wrote: “It was suggested that, if the slave-market were supplied with articles of European manufacture by legitimate commerce, the trade in slaves would become impossible…This could only be effected by establishing a highway from the coast into the centre of the country.”

Livingstone was Kingdom-focused, stating: “I place no value in anything that I may possess except in relation to the Kingdom of Christ. I shall promote the glory of Him to whom I owe all my hopes in time and eternity.” Dugard comments of Livingstone, that “it was his habit each Sunday to read the Church of England service aloud…he prayed on his knees at night and read his Bible daily.”

People are often amazed at how Livingstone, who could have chosen a comfortable life, instead sacrificed his life to care for the African people. In speaking to the Cambridge faculty and students, Livingstone memorably commented,

People talk about the sacrifice that I have made in spending so much of my life in Africa. Can that be called a sacrifice which is simply paid back a debt as a small part of the debt we owe to God that we can never repay?

Though his body was laid to rest at Westminster Abbey in London, his heart was buried in Africa. Florence Nightingale said that God has taken away the greatest man of his generation, for Dr. Livingstone stood alone. May God give us Livingstone’s heart of love for Africa.

Leave a Reply