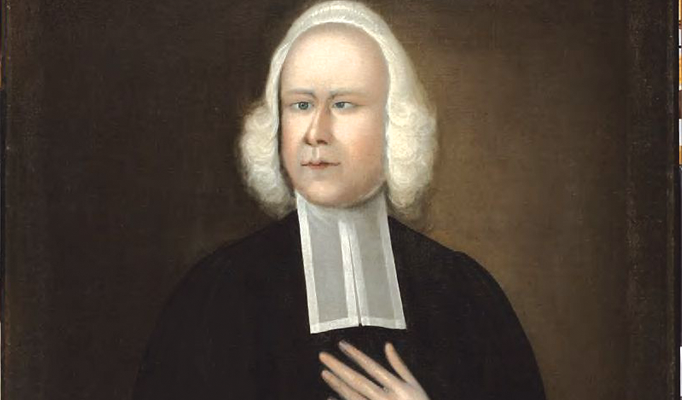

When is the last time that your pastor had to be hoisted, like George Whitefield, through a window into your crowded church building, because there was no other way in? The Rev. George Whitefield (1714 – 1770) took part in a Great Awakening that is still impacting many congregations today. Charles Spurgeon called Whitefield “all life, fire, wing, force.”

After being ordained at age 21, Whitefield was accused of driving fifteen people mad in his first sermon. His Gloucester Bishop Benson ironically said that he wished that the madness might not be forgotten before next Sunday. The so-called madness was actually people waking up to the life-changing love of Christ. In his 34 years of ordained ministry, Whitefield preached more than 18,000 sermons to perhaps ten million people. Dr. Thomas S. Kidd holds that “perhaps he was the greatest evangelical preacher the world has ever known.” Because of his speaking gift, Whitefield’s nickname was the Seraph (type of Angel). He was once described by UK Prime Minister Lloyd George as the greatest popular orator produced by England. David Hume, a famous agnostic commented that “Mr Whitefield is the most ingenious preacher I ever heard. It is worth going twenty miles to hear him.” The famous English actor, David Garrick, held that Whitefield could “make men weep and tremble by his varied utterances of the word ‘Mesopotamia’.” (the ancient land that Abraham came from)

While in Oxford, he became close friends with John and Charles Wesley who helped him in the spiritual disciplines. After reading the book, The Life of God in the Soul of Man, Whitefield became convinced that good works would not earn him heaven: “God showed me that I must be born again….” Experiencing the new birth gave him a fresh love of the beauty of spring: “At other times, I would be so overpowered with a sense of God’s infinite majesty that I would be compelled to throw myself on the ground and offer my soul as a blank in his hands, to write on it what he pleased.” The new birth became the heart of an unprecedented evangelical revival.

Whitefield accepted the Wesleys’ invitation to join them as missionaries in Savannah, Georgia. He waited however for months to sail to Georgia with his patron General Oglethorpe. During this delay in England, tens of thousands came to hear him preach about the new birth. After passionately preaching outside to 10,000 miners in Kingswood, near Bristol, he wrote: “The fire is kindled in the country and I know all the devils in hell shall not be able to quench it.” Whitefield became the Billy Graham of the 18th century, preaching that all people need to be born again. He was very countercultural, doing the unthinkable thing of preaching without notes, in fields, to tens of thousands. In 18th century England, sermons were only supposed to be given in church buildings. Because of the fear of revolution, the worst thing you could be accused of was enthusiasm. Whitefield sought to reach the heart as well as the head, saying that many people “were unaffected by an unfelt, unknown Christ.”

On his way to Georgia, Whitefield had such a strong voice that when the two other ships travelling with them drew close, he was simultaneously able to preach to all the people on the three ships. At a time when travel was precarious, Whitefield made seven visits to America, 15 to Scotland, and two to Ireland. Whitefield was the best-known person to have travelled extensively in the 13 American colonies. By 1740, he had become the most famous man in both America and Britain, at least the most famous aside from King George II.

Whitefield was radically generous even to a fault. Wherever revival meetings took place, Whitefield received offerings, including from Benjamin Franklin, to help with the most famous orphanage in North America, Bethesda, in Savannah, Georgia.

Benjamin Franklin scientifically established that Whitefield was able to preach to 30,000 people without a microphone. He became Whitefield’s publisher, and a close friend and ally. Between 1740 and 1742, Franklin printed 43 books and pamphlets dealing with Whitefield and the evangelical movement. He even built Whitefield a building for preaching that became the University of Pennsylvania. That is why there are statues of both Franklin and Whitefield as co-founders of the University of Pennsylvania. Franklin commented: “It was wonderful to see the change soon made in the manners of our inhabitants. From being thoughtless or indifferent about religion, it seemed as if all the world was growing religious, so that one could not walk through the town in an evening without hearing psalms sung in different homes in every street.”

The Bishop’s Commissary (superintendent), Alexander Garden, in Charleston was offended by Whitefield’s article challenging slave owners over mistreatment of slaves, and by Whitefield’s preaching both in other parish areas and among other denominations. Garden declared that the slave owners were going to sue Whitefield for libel. During his sermon, Garden attacked Whitefield, and refused him communion, before dragging Whitefield into an ecclesiastical court trying to defrock him. Jonathan Edwards of Northhampton, a co-leader in the Great Awakening, wrote: “Whitefield was reproached in the most scurrilous and scandalous manner…I question whether history affords any instance paralleled with this, as so much pains taken in writing to blacken a man’s character, and render him odious.” Whitefield did not let criticism stop him, saying “The more I am opposed, the more joy I feel.”

On a Sunday morning in Philadelphia, Whitefield preached to some 15,000 people. He then attended an Anglican Communion service where Commissary Cummings publicly denounced him and his followers. He followed this right after with preaching a farewell sermon to an outdoor assembly of 20,000. The relentless pace was brutal to Whitefield’s health.

During his four years away from England, the Gentleman’s Magazine and other English newspapers listed George Whitefield as having died.

He changed so many lives that even the English upper classes began to give Whitefield a hearing. Lord Bolingbroke, after hearing Whitefield at Lady Huntington’s place, wrote: “Mr. Whitefield is the most extraordinary man of our times. He has the most commanding eloquence I ever heard in any person…” One Anglican minister claimed that Whitefield had set England on fire with the devil’s flames. Whitefield countered. “It is not a fire of the Devil’s kindling, but a holy fire that has proceeded from the holy and blessed Spirit. Oh, that such a fire may not only be kindled, but blow up into a flame all England, and all the world over!”

Dying at 55, Whitefield had been used to set many people on fire with love for Christ. He memorably prayed: “O that I could do more for Him! O that I was a flame of pure and holy fire, and had a thousand lives to spend in the dear Redeemer’s Service.” Whitefield was all about awakening to the new birth. We, in Canada, also need to wake up to the fire of Christ. We too need to recapture the priority of the new birth. Have you, like Whitefield did, awoken yet to the new birth?

Rev. Dr. Ed and Janice Hird, co-authors of For Better, For Worse: discovering the keys to a lasting relationship.

Leave a Reply