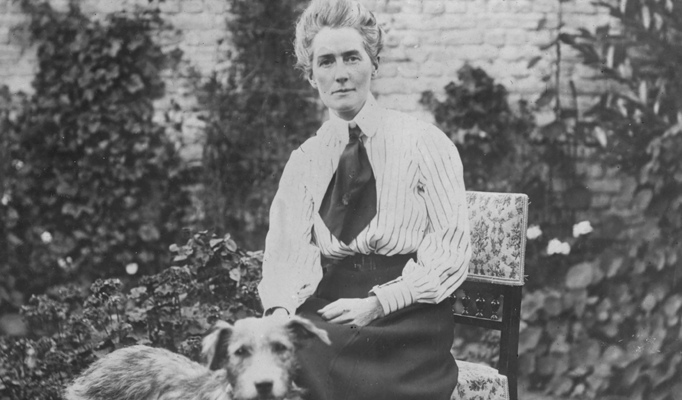

Are you inspired by the lives of great men and women of faith? They often appear so far above us in greatness and deed. Edith Cavell was an ordinary country girl who grew to be known as a pioneer, patriot, spy and heroine. Her life began with such simple ideals: a love for God and a desire to serve others.

Edith Louisa Cavell was born in 1865 in Norfolk, England, the eldest child of Louisa and Frederick Cavell. She had two sisters, Florence and Lilian, and a brother, Jack. Their father was the local vicar. Edith’s love for God was rooted in fertile soil, like a tiny seedling awaiting the warmth of the sun. Because of her love for God, she longed to serve others. Edith searched for opportunities at home to bless those in her small rural village. As a young girl, she carried homemade pots of jam to her neighbours, and when a new Sunday school room was needed, she painted cards of wildflowers and sold them to raise funds.

Commitment & service in the day-to-day village opportunities became Edith’s stepping-stones, leading to an unwavering determination and faith that grounded her later in life.

Her first employment was as a governess for a Lawyer in Brussels. Then, in 1895, after a season in Norfolk to care for her sick and ageing father, Edith believed God was calling her to become a nurse.

Her heart’s longing was always to serve God by serving others. Training to become a nurse meant long hours and hard work. Edith started at seven every morning, doing the practical chores in the hospital, and she ended her day at 9 pm after two hours of study. In 1897, Typhoid fever broke out in London where Edith was training. Still, she continued working with enormous risk to her own life.

Because of her earlier connection in Brussels, she was offered a job by a surgeon. Although nursing was still considered unfit work for women, nurses in Britain were considered of the highest calibre. The surgeon needed an English nurse who could speak French and train Belgium women.

Edith returned to Brussels to set up her nursing clinic, visiting home in Norfolk every summer to help her now widowed mother. During one of these visits home, she received a letter warning of the imminent occupation threat in Belgium. The First World War had begun. Her friends advised her to not return, but Edith had a great sense of duty and commitment towards others. She would not leave her nursing staff to fend for themselves.

When Brussels became occupied, many allied soldiers, trapped behind enemy lines, hid out in the forests or found shelter with a growing number of patriots. Some of these injured men were brought to Edith’s clinic, where she hid and nursed them. A network of people aided in helping these men find safe passage out of Belgium and back to England or France. It was a criminal offence to help allied soldiers, and if caught, the penalty was death by a firing squad.

Edith’s clinic consisted of four old terraced houses, which worked perfectly for hiding the men in one attic or another. Even Edith’s nurses were not aware of the risks she was taking. Her friends pleaded with her to stop, but Edith felt that it was her duty to help everyone – allied or not.

She was finally caught and arrested. At her trial, her unwillingness to minimize the truth about her activities sealed her fate. Her final evening was spent writing letters to her mother and Grace, a young woman struggling with a morphine addiction, whom she befriended. “I worried about you at first, but I know that God will do for you abundantly above all that I can ask or think, and he loves you so much better.”

Edith resolutely reaffirmed her faith in God by underlining the following passage in her book, The Imitation of Christ: “There is none to help me, none to deliver me and save me, but thou, O Lord God, my Saviour, to whom I commit myself and all that is mine, that Thou mayest keep watch over me and bring me safe to life everlasting.”

The Reverend Stirling, who was allowed to continue his duties throughout the occupation, visited Edith that last evening. Alone, they spoke about things that concerned Edith the most. She quietly assured the reverend that she trusted in the finished work of Christ and the Grace of God. She added:

“Standing in view of God and eternity, I realize that patriotism is not enough…one must love all men and hate none. I have no hatred or bitterness against anyone.”

Edith Cavell is remembered for saving the lives of soldiers from both sides without discrimination and helping some 200 Allied soldiers escape from German-occupied Belgium. Her life illustrates what it truly means to love your neighbour as yourself. Edith’s legacy of faith and conviction to follow God, even in the face of evil, stands as an enduring testimony of what God can accomplish through the simple commitment of a young girl.

Leave a Reply