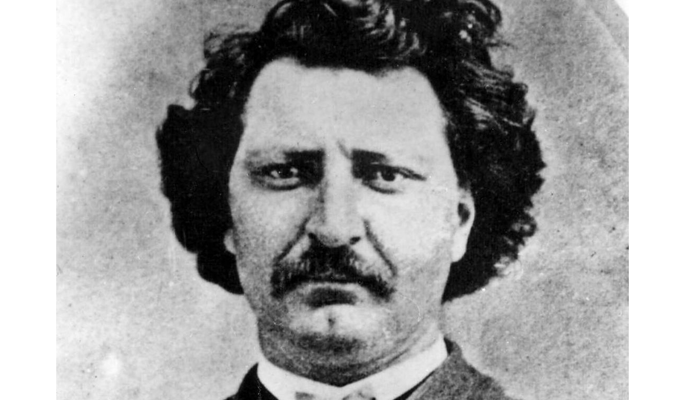

Nicholas Davin and Louis Riel were two of our most famous, or I should say infamous, and complicated, Canadian pioneers. Their two lives were deeply entangled in a life-and-death battle for the soul of Canada. Born in 1844, Riel, who had trained to be the first Metis priest, was very Christ-centered, praying in his diary: “Lord Jesus, I love you. I love everything associated with You.” Just before his ordination was to have taken place, he had secretly become engaged to Marie Julie Guernon, only to have the engagement quashed by her racist parents.

Returning to Winnipeg with no wife and no ordination, he discovered social devastation among his Metis people. A locust plague of biblical proportions had devastated the Manitoba crops, bringing widespread starvation. After taking over the Hudson Bay Company’s Fort Garry, Riel successfully forced Prime Minister John A. MacDonald to recognize Metis land rights, and to accept Manitoba into Confederation as a full province, and not just another territory. Riel, who loved Canada, stated to the Federal negotiator Donald Smith: ‘We want only our just rights as British subjects, and we want the English to join us simply to obtain these.’

In the summer of 1870, two American leaders, Nathanial F. Langford and ex-governor Marshall of Minnesota visited Riel at Fort Garry. They promised Riel four million in cash, guns, ammunition, mercenaries and supplies to maintain himself until his government was recognized by the United States. Riel declined. After William O’Donohue ripped down the Union Jack, Riel immediately reposted it with orders to shoot any man who dared touch it. Riel proclaimed that the Metis were ‘loyal subjects of Her Majesty the Queen of England’. On May 12, 1870, the Manitoba Act, based on the Métis ‘List of Rights’ was passed by the Canadian Parliament.

The tragedy of the Red River Rebellion was the Riel-authorized shooting of Thomas Scott. “The Metis are a pack of cowards,” boasted Thomas Scott, “They will not dare to shoot me.” If it was not for Riel’s sanctioning of the tragic shooting of the Orangeman Thomas Scott, he might have ended up in John A Macdonald’s federal Cabinet. Because of Thomas Scott’s death, Eastern Canada would settle for nothing less than Riel’s head on a platter. John A. Macdonald’s promised amnesty for Riel never came through.

After fleeing to the United States, Riel was then elected in his absence as a Manitoba Conservative MP. The Quebec legislature in 1874 passed a unanimous resolution asking the Governor-General to grant amnesty to Riel. That same year, after Louis Riel’s re-election as MP, he entered the parliament building, signed the register, and swore an oath of allegiance to Queen Victoria before slipping out to avoid arrest. The outraged Canadian House of Commons expelled him by a 56-vote majority. Passionate prayer however kept Riel from giving up on his mission to the Metis: “Jesus, author of life! Sustain us in all the battles of this life and, on our last day, give us eternal life. Jesus, give me the grace to really know your beauty! Grant me the grace to really love You. Jesus, grant me the grace to know how beautiful You are; grant me the grace to cherish You.”

In 1884, Riel returned to Batoche, Saskatchewan from exile in Montana with his family. Because of the slaughter of the buffalo, the Metis were starving. Riel sent a petition to Ottawa demanding that the Metis be given title to the land they occupied and that the districts of Saskatchewan, Assiniboia (Manitoba) and Alberta be granted provincial status. The Federal Government instead set up a commission. In the absence of concrete action, Riel and his followers decided to press their claims by the attempted capture of Fort Carlton.

Riel’s cause however was militarily doomed. Most of the 250 Metis had shotguns or old muzzle-loaders, but a few had only bows and arrows. My great-grandfather Oliver Allen was among the Toronto militia who were shipped on the Canadian Pacific Railway to quickly defeat Riel at Batoche. An American Lieutenant Arthur Howard used a Gatling gun with 1,200 rounds a minute, on loan from the US Army. The battle did not last long.

While conquering Riel, my great-grandfather met my great-grandmother Mary Mclean who was sympathetic to Louis Riel. Shortly after, my great-grandparents Oliver and Mary married and relocated to start a new life in BC.

Nicholas Flood Davin was Riel’s archenemy, treating him as a traitor, calling for his hanging. “Riel is not a hero,” said Davin. “…If Riel is not hanged, then capital punishment should be abolished.” Born in Kilfinane, Ireland, Davin was a war correspondent in Europe before moving to Toronto in 1870. Then, Davin became editor in 1883 of the brand-new Regina Leader newspaper. He insightfully commented that ‘the pulpit occupied almost the whole ground occupied by the newspaper today…The Editor has superseded the preacher.” Davin, the future federal MP, wrote the infamous confidential Davin Report which resulted in our First Nations being subjected to the Residential School tragedy. When rushing into starting native residential schools, Davin disregarded advice not only from the local Catholic hierarchy, but also from the Anglican Bishops and Metis elders. They all said ‘no’. Davin’s exploration in the USA of the allegedly successful American Carlisle School lasted less than 72 hours before he went back by train to Winnipeg. Quick fixes often bring lasting harm.

After taking journalism at a women’s college in Kirkland Ontario, Mary McLean served as Davin’s reporter covering the Louis Riel crisis. Davin told McLean to get an interview with Louis Riel or don’t come back. (Ed’s late Uncle Don Allen, who was passionate about history, often told us about this period, noting how sympathetic his grandmother was to Riel’s plight). Davin carried on the British tradition of not listing the byline names of the reporters who wrote for the Regina Leader. This was helpful for McLean in protecting her from arrest by the RCMP when she snuck in disguised as a Roman Catholic priest confessor, Father Alexis Andre. McLean quotes Davin “the officer in command of the Leader (saying) ‘An interview must be had with Riel if you have to outwit the whole police force of the North-West’.” Because Davin protected her anonymity, some writers like CB Koester and his fellow playwright Ken Mitchell have popularized the myth that Davin himself disguised himself as that priest. (In May 1982, Ed and Janice spent a week with his late Uncle Don Allen who carefully explained about his grandmother’s interview with Louis Riel.)

The University of Western Ontario changed its documentation to acknowledge that Mary McLean was the reporter who interviewed Riel, disguised in a priest’s garb. Even the Regina Leader Post newspaper recently acknowledged that Mary Mclean was the actual reporter in this incident

After having two children with Davin, his mistress Kate Simpson-Hayes gave the children away and became a reporter in Winnipeg. When Davin then married Eliza Reid, he brought his six-year-old son Henry to live with him as a ‘nephew’ but was unable to locate his daughter. In Davin and Simpson-Hayes’ final argument over the daughter, she said to him: “You go your way. I’ll go mine,” symbolically pointing to the Winnipeg Free Press building. Davin was so crushed that he bought a gun and shot himself on Oct 18, 1901, at the Winnipeg Clarendon Hotel. Both died tragically, Riel on the end of a noose, Davin by his own hands.

Riel never took his eyes off Jesus. Before Riel died, he prayed in his diary: “Lord Jesus, I love you. I love everything associated with You…Lord Jesus, do the same favour for me that You did for the Good Thief; in Your infinite mercy, let me enter Paradise with You the very day of my death.”

The tragic ending to the complicated lives of both Riel and Davin reminds us that our Canadian history has much pain and trauma which can only be resolved through a fresh start. May Jesus the Prince of Peace use us to humbly bring healing to our Indigenous and Metis Canadians.

Leave a Reply