Beethoven once said: “Handel was the greatest composer that ever lived. I would uncover my head and kneel before his tomb.” King George III called Handel “the Shakespeare of Music.” George Bernard Shaw commented that “Handel is not a mere composer in England: he is an institution. What is more, he is a sacred institution.”

In North America and England, at the very least, Handel’s Messiah has become the most popular performed, recorded and listened to choral work. Many people stereotype Handel’s Messiah as Christmas music. For Handel, the Messiah was an Easter event that told not merely of birth but also of death and resurrection.

Early talent

George Friedrich Handel was born in Halle, Germany within a month of Johanne Sebastian Bach (1685). Handel’s father was a barber-surgeon who hated music and wanted his son to become a successful lawyer. His aunt Anna gave Handel a spinet harpsichord that they hid in Handel’s attic, wrapping each string with thin strips of cloth, so that Handel could play undetected.

When Handel was eight or nine, the Duke of Weissenfels heard him play the postlude to a church service. summoned the boy’s father and told him he ought to encourage such talent. His only teacher was Friedrich Wilhelm Zachow, a most learned and imaginative musician and teacher, who instilled in his young pupil a lifelong intellectual curiosity. At age 11, Handel entered a musical contest at the Berlin court of the Elector with the famous composer Buononcini, and won.

A move to England from Germany

When Handel moved to England in 1712, it was a beehive of musical activity with Italian opera ruling the day. Within the next thirty-year period in England, Handel wrote about 40 operas and 26 oratorios. He did not play to easy audiences. If opera attendees felt bored in Handel’s day, they would often start loud conversations, and walk around freely. It was also a custom for them to play cards and eat snacks during the opera.

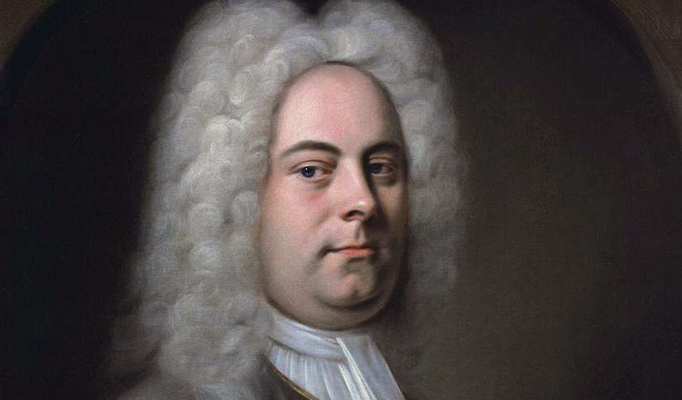

Jane Smith & Betty Carlson wrote, Handel “…was an inviting target for critics and for satire. He was a foreigner, and an individual no one could help noticing. He had large hands, large feet, a large appetite, and he wore a huge white wig with curls rippling over his shoulders. Handel spoke English rather loudly in a colourful blending of Italian, German, and French. He was temperamental, he loved freedom, and he hated restrictions placed on his art…”

Charles Burney, who later sang and played under him, told how Handel once raged at him when he made a mistake, “a circumstance very terrific to a young musician.” But when Handel found that his mistake was caused by a copying error, he apologized generously (“I pec your parton – I am a very odd tog”, he said in Germanic English).

Struggles

Handel also struggled with his weight, a problem about which critics mercilessly teased him. As Romain Rolland has tried to explain it: “He was surrounded by a crowd of bulldogs with terrible fangs, by unmusical men of letters who were likewise able to bite, by jealous colleagues, arrogant virtuosos, cannibalistic theatrical companies, fashionable cliques, feminine plots, and nationalistic leagues…Twice he was bankrupt, and once he was stricken by apoplexy amid the ruin of his company. But he always found his feet again; he never gave in.”

The situation was so bleak in 1741 that just before he wrote the Messiah, he had seriously considered going back to Germany. But instead of giving up, he turned more strongly to God. Handel composed the Messiah in 24 days without once leaving his house. During this time, his servant brought him food, and when he returned, the meal was often left uneaten. While writing the “Hallelujah Chorus”, his servant discovered him with tears in his eyes. He exclaimed, “I did think I did see all Heaven before me, and the great God Himself!!”

Destined to become one of the greatest

As Newman Flower observes, “Considering the immensity of the work, and the short time involved in putting it to paper, it will remain, perhaps forever, the greatest feat in the whole history of musical composition.”

At a Messiah performance in 1759, honouring his seventy-fourth birthday, Handel responded to enthusiastic applause with these words: “Not from me – but from Heaven comes all.” In his last years he worshipped twice every day at St. George’s Church, Hanover Square, near his home.

The Messiah was first performed in Dublin in 1742, and immediately won huge popular success. In order to have room enough for the people a request was sent far and wide, asking, “The favour of the Ladies not to come with hoops this day to the Music Hall in Fishamble Street. The Gentlemen are desired to come without their swords.” This is how the Dublin Newspaper reported the event: “…The best Judges allowed it to be the most finished work of Musick. Words are wanting to express the exquisite Delight it afforded to the admiring crowded Audience. The Sublime, the Grand, and the Tender, adapted to the most elevated, majestic, and moving Words, conspired to transport and charm the ravished Heart and Ear…” Handel could have made a financial killing from the Messiah, but instead he designated that all the proceeds would go to charities.

In contrast to the Irish, the English did not initially like the Messiah. This oratorio, after all, had no story. The soloists had too little to do, and the chorus too much. It was different, and the audience wasn’t ready for it. Jennens who wrote the script didn’t like it either. He commented: “Handel’s Messiah has disappointed me, being set in great haste, though he said he would be a year about it and make it the best of all his Compositions. I shall put no more Sacred Works into his hands, thus to be abused.”

Twenty-five years later, Handel’s Messiah was so popular with the English that they almost rioted, while waiting to hear it at Westminster Abbey. People screamed, as they feared being trampled. Others fainted. Some threatened to break down the church doors.

The Bible in the theatre!

Handel’s use of biblical words in a theatre was revolutionary, and those who opposed him went to great extremes to keep his oratorios from being successful. For example, certain self-righteous women gave large teas or sponsored other theatrical performances on the days when Handel’s concerts were to take place in order to rob him of an audience. As well, his enemies hired boys to tear down the advertisements about Handel’s Messiah. One opponent wrote to a newspaper asking, “if the Playhouse is a fit Temple…or a Company of Players fit Ministers of God’s Word.” This person saw the Messiah as “prostituting sacred things to the perverse humour of a Set of obstinate people.”

In contrast, the famous preacher John Wesley liked Handel’s Messiah. He wrote: “In many parts, especially several of the choruses, it exceeded my expectation.” One clergy, William Hanbury, in 1759 said that you could hardly find an eye without tears in the whole audience.

The tradition of standing for the Hallelujah Chorus

King George II of England was so deeply stirred with the exultant music, that when the first hallelujah rang through the hall, he rose to his feet and remained standing until the last note of the chorus echoed through the house. From this began the custom of standing for the Hallelujah Chorus. When a nobleman praised Handel as to how entertaining the Messiah was, Handel replied, “My Lord, I should be sorry if I only entertained them; I wished to make them better.”

What is it about the Messiah that makes it so popular? Many scholars point to the spaciousness in Handel’s music, the dramatic silences, and the stirring contrast. In his biography Stanley Sadie commented that the music of Handel’s, is a blend of different styles: English church music (especially the choruses), the German Passion-music tradition, the Italian melodic style. In fact, three of the choruses are arranged from Italian love-duets which Handel had written thirty years before.

In 1759 the almost blind Handel conducted a series of 10 concerts. After performing the Messiah, he told some friends that he had one desire – to die on Good Friday. “I want to die on Good Friday,” he said, “in the hope of rejoining the good God, my sweet Lord and Saviour, on the day of His resurrection.”

On Good Friday, he bid good-bye to his friends and died the very next day on Holy Saturday, April 14, 1759. Handel was fittingly buried in Poet’s Corner at Westminster Abbey. A close friend of Handel’s, James Smyth, said: “Handel died as he lived – as a good Christian, with a true sense of his duty to God and man, and in perfect charity with all the world…”

May the words and music of Handel’s Messiah help us experience the intimacy of Handel’s relationship with His Messiah, Jesus of Nazareth.

You can hear Handel’s Messiah around the Lower Mainland in December.

Dec 9, 7:30 pm, Belle Voci & CSO Baroque Ensemble present Messiah in the Valley – at St. James Catholic Church, Abbotsford. Info & Tix: https://chilliwacksymphony.com

Dec 10, 2 pm, Handel’s Messiah – Handel’s Messiah at Central Heights Church, Abbotsford. Two choirs (Valley Festival Singers & Pacific Spirit Choir) will join to present this timeless work. Conductor: Gerry van Wyck, Concertmaster: Calvin Dyck. Info: https://www.calvindyck.com.

Dec 11, 7:30 pm, Belle Voci & CSO Baroque Ensemble present Messiah in the Valley – at Fleetwood Christian Reformed Church, Surrey. Info & Tix: https://chilliwacksymphony.com.

Leave a Reply