Everyone nowadays loves the Salvation Army (the Sally Ann), but such admiration was not always universal.

Violence and bloodshed was the order of the day when William Booth first reached out to the down-and-out in East London, England. Few people today realize that one of the main purposes of the famous Sally Ann bonnet was to protect the heads of wearers from brickbats and other missiles. So many people used to buy rotten eggs to throw at the Sally Ann bonnets that these rancid eggs became renamed in the market place as Salvation Army eggs.

In 1880, heavy sticks crashed upon the Salvation Army soldiers’ heads, laying them open, and saturating them in blood. One sister was injured so badly she died within a week. In1882, it was reported that 669 soldiers and officers had been brutally assaulted, 251 of them women and 23 children under 15.

In Canada too, the Salvation Army was persecuted. In Hamilton, Ontario, the Salvation Army officers were beaten. In Quebec City, 21 Salvation Army soldiers were seriously injured, an officer stabbed in the head and a drummer had his eye gouged out. In Newfoundland, the soldiers were attacked with hatchets, knives, scissors and darning needles. One woman Salvationist was attacked by a gang of three hundred ruffians, thrown into a ditch and trampled on. She managed to crawl out only to be thrown in again, as other women were shouting ‘Kill her! Kill her!

Jail sentences for being in a Salvation army band

Initially police blamed the Salvation Army for being persecuted. In numerous parts of England, playing in a Salvation Army Marching Band was punishable with a jail sentence! During 1884, no fewer than 600 Salvationists had gone to prison in defense of their right to proclaim good news to the people through music and word. In Canada too, nearly 350 officers and soldiers served terms of imprisonment for spreading the gospel. Despite persecution, the Salvation Army continued to grow. The early Salvation Army ‘jailbirds’ described their handcuffs as heavenly bracelets. It is little wonder that the Salvation Army eventually developed such a powerful prison ministry.

Redeeming the community

One of William Booth’s mottoes was ‘go for souls and go for the worst!’ A local English newspaper The Echo commented that the Salvation Army largely recruited the ranks of the drunkards and wife-beaters and woman home-destroyers. Many of us remember from when we were children the song: ‘Up and down the City Road, In and out the Eagle; That’s the way the money goes, Pop goes the weasel’! Few of us realized we were singing about the famous Eagle Tavern, just off City Road in London. ‘Pop goes the weasel’ was cockney slang for the alcoholic who was so desperate for a drink that he would even pawn (pop) his watch (weasel). Ironically, the Salvation Army bought the Eagle Tavern and turned it into a rehabilitation centre. The Lion and Key public house in East London became known as ‘The Army Recruiting Shop’.

Worshipping outside of the traditional

William Booth shocked the world by conducting worship with tambourines and fiddles, instead of the traditional church organ. To make up for the Salvation Army’s lack of church buildings, General Booth bought circus buildings, skating rinks, and theatres.

In response to such bold innovation, one newspaper columnist claimed in 1883 that ‘The Salvation Army is on its last legs, and in three weeks it may be calculated it will come to an end.’

In the beginnings, the Salvation Army was essentially a youth movement, with seventeen-year-olds commanding hundreds of officers and thousands of seekers. Archbishop Tait of Canterbury was so impressed by this youth movement reaching the poor, that he set up a commission which unsuccessfully tried to adopt the Salvation Army as an Anglican society.

Over time the Salvation Army began to earn respect from both the churched and the unchurched, and from all segments of society. Even Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle sent them a message: ‘Her majesty learns with much satisfaction that you have with other members of your society been successful in your efforts to win many thousands to the ways of temperance, virtue, and religion.’ By persevering in reaching out to the poor, William Booth and the Salvation Army became known as the champions of the oppressed. Like no other individual in 19th-century England, Booth dramatized the war against want, poverty and destitution.

Soup, soap and salvation

It was not by accident that William Booth’s message became linked with ‘soup, soap, and salvation’! Every Salvation Army soldier was taught from the beginning to see themselves as servants of all, practicing the ‘sacrament’ of the Good Samaritan. The famous preacher Charles Spurgeon once said, ‘If the Salvation Army were wiped out of London, five thousand extra policemen could not fill the place in the repression of crime and disorder.’ On June 26, 1907, in recognition of his incalculable impact on the poor, William Booth received the degree of Doctor of Civil Law from the University of Oxford.

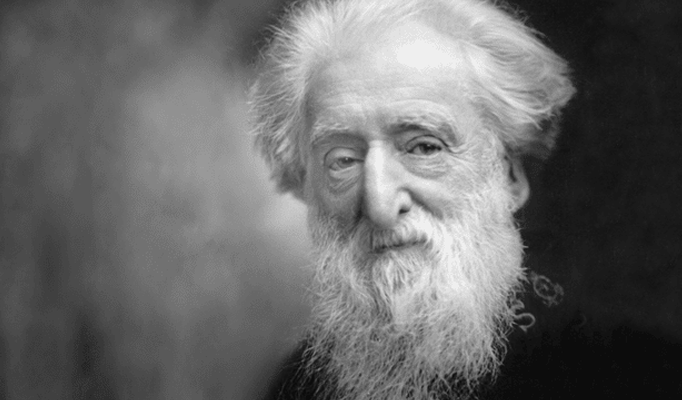

Creativity, courage and spritual fatherhood

Throughout his life , William Booth showed remarkable creativity and courage. He was one of the world’s greatest travellers in his day, visiting nearly every country in the world. Even at age 78, General Booth was described as ‘…a bundle of energy, a keg of dynamite, an example of perpetual motion.’

His fellow soldiers saw Booth as a man to follow to their death, if need be. William Booth was truly a spiritual father to the fatherless. His son Bramwell held that his dad’s greatest power lay in his sympathy, his heart a bottomless well of compassion.

A Maori woman described William Booth as ‘the great grandfather of us all – the man with a thousand hearts in one!’ Mark Twain said, ‘I know of no better way of reaching the poor than through the Salvation Army. They are of the poor, and know how to get to the poor.’

The Rev. Dr. Ed and Janice Hird are co-authors of For Better, For Worse: discovering the keys to a lasting relationship.

Leave a Reply