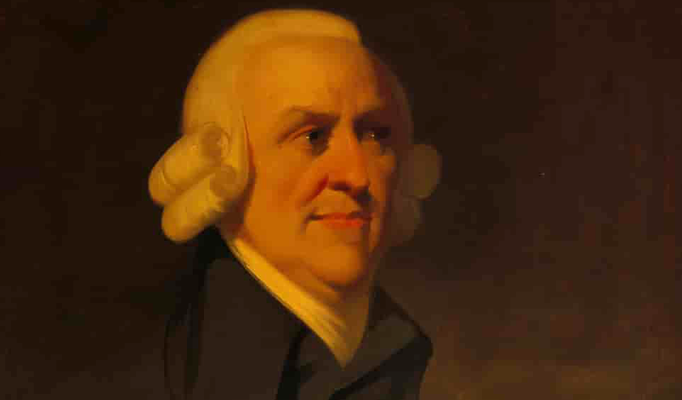

Many people nowadays have little idea how Adam Smith’s economic ideas have shaped their lives for good. Can a rediscovery of the real Adam Smith rescue our muddled Canadian economy?

In 1776, Smith’s second book The Wealth of the Nations was so popular that he became known as the Father of Economics and the Father of Capitalism. For some people today, Capitalism has become a negative word associated with Scrooge-like greed and cutthroat business practices. Karl Marx blamed capitalism for all the world’s ills. Can capitalism instead embrace the compassionate vision in Charles Dickens’ book A Christmas Carol?

Because Smith was a devout Christian economist, God was mentioned a total of 403 times between his two books, including his lesser-known book The Theory of Moral Sentiments. Biblical economics is based on our being faithful stewards, realizing that all things come from God, and of his own have we given him (1 Chronicles 29:14). Stewardship in the Greek is the same word as economics (oikonomos, manager of the oikos, the house). Smith wanted everyone to earn a decent living, saying ‘No society can surely be flourishing and happy of which the far greater of the members are poor and miserable.’ He lamented how the poverty and poor health care in the Scottish Highlands resulted in many a mother having only two of her children survive after giving birth to twenty babies. With Canada’s standard of living suffering from governmental and economic mismanagement, perhaps it may be time to revisit the economic wisdom of Adam Smith. Might a rediscovery of the Protestant work ethic of diligence, thrift and efficiency help Canada get back on track?

What might happen in Canada if we once again rewarded hard work rather than punishing it with excessive taxation and regulations? Smith wrote about the Man of system who bureaucratically treated people as if they are chess pieces. In contrast, Smith held that economic freedom with free markets and free trade brings economic progress. Smith observed how God transforms private interest into public good by his invisible sovereign hand.

Born in 1723 in Kirkcaldy, Scotland, Adam Smith never knew his father who had died five months before his birth. Smith regularly attended the local church with his devout mother, Margaret. His strong Christian faith is often ignored or minimized by modern economists. He never married, living with his mother until her death in 1784. He then died himself six years later. You cannot really understand Adam Smith without appreciating his 1759 book, The Theory of Moral Sentiments:

As to love our neighbour as we love ourselves is the great law of Christianity, so it is the great precept of nature to love ourselves only as we love our neighbour, or what comes to the same thing, as our neighbour is capable of loving us.

As Christians, our financial choices need to be shaped by the love of neighbour as ourselves rather than the love of money. The golden rule is God’s golden way economically. When people matter more than profits, everyone wins.

Adam Smith was not just a philosopher and economist. He was also an early psychologist and sociologist who served at Glasgow University as Professor of Moral Philosophy. He was such an academic rock star in Glasgow that the university bookstore even sold a bust of his head during his lifetime. Smith was fascinated about what made people tick, especially how emotions/sentiments affected our life choices and ethical decisions. Influenced by his lifelong friend David Hume, Smith held that our emotions and imagination shape us far more than our apparent rationality. Like Hume, Smith pioneered the modern scientific method where technology, business, and society are advanced through careful experimental observation.

Unlike Hume, Smith retained a strong Christian worldview as he embraced science. With most of his students training to become ordained clergy, he taught them extensively about natural theology, how God our creator impacted our natural world:

…every part of nature, when attentively surveyed, equally demonstrates the providential care of its Author, and we may admire the wisdom and goodness of God, even in the weakness and folly of man.

Smith was struck by the miraculous order of God’s good universe. He called the universe God’s machine, designed to produce at all times the greatest quantity of happiness in us. Romans 8:28 reminds us how all things work together for the good. In The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Smith commented that:

…all the inhabitants of the universe, the meanest as well as the greatest, are under the immediate care and protection of that great and all-wise being who directs all the movements of nature, and who is determined by his own unalterable perfections to maintain in it at all times the greatest possible quantity of happiness.

Since he was fatherless, Smith deeply appreciated that God was indeed our heavenly Father. He commented that ‘the very suspicion of a fatherless world must be the most melancholy of all reflections’, leaving us with nothing but endless misery and wretchedness.

All the economic prosperity in the world, said Smith, can never remove the dreadful gloominess of a world without God our Father. Smith taught that with this conviction of a benevolent heavenly Father, all the sorrow of an afflicting adversity can never dry up our joy. Smith, who sometimes suffered from depression, knew that because he was not cosmically alone, he had reason to keep going. While there is weeping in the night, there is indeed joy in the morning. (Psalm 30:5) After experiencing academic burnout, he left Glasgow University, serving as a European tutor for Henry Scott, the future Duke of Buccleuch. While in Paris, he became friends to Voltaire and the French physiocrat economists, led by Dr. Francois Quesnay, the Royal Physician to King Louis XV. After the tragic death of Henry Scott’s younger brother, Smith returned home, never to again visit Europe.

Smith held that we need to submit our will to the will of the great director of the universe. While Smith as an Oxford-trained academic was very private about his emotions, he clearly taught that God deserved our unlimited trust, and ardent & zealous affection.

No conductor of an army can deserve more unlimited trust, more ardent and zealous affection, than the great conductor of the universe.

Both economics and theology for Smith needed to be practical. He said that while contemplating God’s benevolent and wise attributes is sublime, we must not neglect the practical call to care for our family, friends and country. As God’s financial stewards, earning money enables us to more effectively care for our family, our neighbour, and our country.

Smith liberated us from medieval mercantilism, which was a zero-sum game of winners and losers where there was no mutual economic growth and value-adding, except in farming. Mercantilism had countries grow wealthier through invading other countries to steal their grain and gold. The mercantilists could not imagine that everyone could win through peaceful international trade. Smith’s economics involved the division of labour, resulting in specialization and free trade between countries and regions. He blamed the profit-driven mercantilism for the dreaded slave trade. Smith realized that free people are better workers, producing better profits. Mercantilism was also so tied down with local guilds that workers were often unable to work in neighbouring towns. Smith envisioned ordinary workers being able to move freely around the country to offer their services. Thanks to Smith’s economic revolution, ordinary people, rather than just the very rich or the government officials, could save up enough money to own their own property. In contrast to mercantilism, Smith held that:

A nation is not wealthy by the childish accumulation of shiny metals, but it is enriched by the economic prosperity of its people.

How might our world be better in 2024 if we embraced Adam Smith’s compassionate, Christian-based economics?

Leave a Reply