Who would have imagined that today’s China probably has more Christians (100 million+) than Communist party members (90 million)? With our senior bishop Dr. Silas Ng reaching many new Chinese believers, we are fascinated by how the gospel initially impacted China.

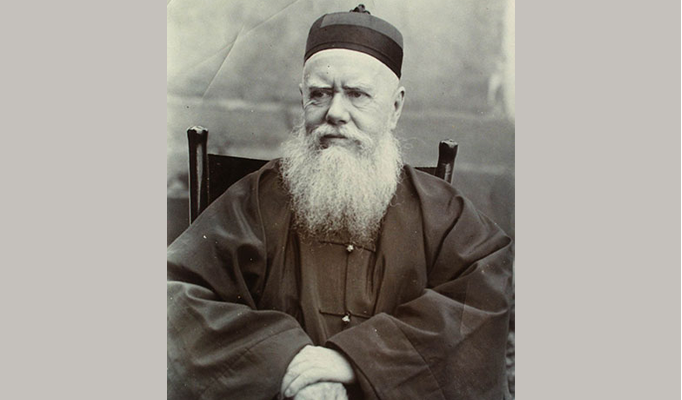

Born in 1832, Hudson Taylor had a burning heart of love for the people of China. His Methodist parents James and Amelia Taylor were fascinated with the Far East. They prayed to God for their newborn baby Hudson, saying “Grant that he may work for you in China.” He did not even attend school until he was 11. By age 13, his schooling was terminated. Even though he loved learning, he suffered a lot with health problems which affected his studies. By age 17, he was outwardly a carefree young man, but inwardly he was rebellious and full of unbelief. After trying to be a good Christian and failing, he initially decided that he could not be saved.

After receiving a pamphlet at age 17 on the finished work of Christ, he was radically converted, developing a great hunger for the bible and a heart for the lost. Hudson soon after received a call to go to China as a missionary where there were only a few hundred believers. This passion was fostered by a little book called China: Its State and Prospects by Walter Henry Medhurst, a London Missionary Society printer serving in China. Hudson read and reread the book until he almost knew it by heart. It saddened him when believers were uninterested in the Great Commission,

“Oh, how it must grieve the heart of God when He sees His children indifferent to the needs of that wide world for which His beloved, His only Son suffered and died.”

At age twenty-one, Taylor sailed off to China for the first time in September 1853. He eventually travelled to China eleven times, involving almost five years of his life on ships. His eyes, never strong, became irritated through the sunshine and excessive dust. In spite of this, he studied the Chinese language around five hours a day. He became fluent in several varieties of Chinese, including Mandarin, Chaozhou, and the Wu dialects of Shanghai and Ningbo.

This deep sacrificial love for Christ and China caused Hudson to do things that some missionaries saw as scandalous. In the 1800s, missionaries to China were expected to stay in missionary compounds in designated coastal cities. Taylor felt called to the unreached inland areas of China, which is why his new missionary agency came to be called China Inland Mission (CIM), now Overseas Missionary Fellowship. Living by faith like his mentor George Mueller, he never asked his supporters for financial offerings, but rather gave a praise report to them after God miraculously provided. Even the well-known Charles Spurgeon and his 10,000-strong congregation cheerfully supported Taylor, often praying with him while he was on furlough. Taylor was persuaded that money given in the name of Jesus was a loan which God would pay back. He firmly believed that “God’s work done in God’s way will never lack God’s supplies.”

Unlike most coastal missionaries, his volunteers were much younger and less highly educated. The most shocking innovation that Taylor and his CIM team did as westerners was to embrace traditional Chinese food, clothing and hairstyle.

“I resigned my locks to the barber, dyed my hair a good black, and in the morning had a proper queue (pigtail with shaven forehead) plaited in with my own, and a quantity of heavy silk to lengthen it out according to Chinese custom.”

Some of Taylor’s CIM missionaries, stationed in Siaoshan, missed western culture so much that they soon returned to western dress. Sadly, they were soon ejected and beaten by the local Mandarin.

Paraphrasing the Apostle Paul, Taylor said,

“Let us in everything not sinful become like the Chinese, that by all means we may save some.”

Taylor embraced missional contextualization years before it became normal in the wider missionary culture.

Memorably, Taylor commented,

“I am not alone in the opinion that the foreign dress and carriage of missionaries, the foreign appearances of chapels, and indeed the foreign air imparted to everything connected with their work has seriously hindered the rapid dissemination of the Truth among the Chinese…We wish to see Chinese Christians raised up – men and women truly Christian, but nonetheless truly Chinese in every sense of the word.”

In 1860, life-threatening hepatitis brought Taylor back to England on medical furlough. While home for four years, he was able to write a colloquial edition of the New Testament written in the Ningbo dialect for the British and Foreign Bible Society. His extended furlough also allowed him to complete his medical degree with the Royal College of Physicians. Ever prolific, he also wrote during his furlough a book called China’s Spiritual Need and Claims in 1865 which was instrumental in generating sympathy for China and volunteers for the mission field. In his book, Taylor wrote:

“Oh, for eloquence to plead the cause of China, for a pencil dipped in fire to paint the condition of this people.”

While at Brighton, England, on June 25, 1865, Taylor at age 33 received the vision, committing himself to raising up missionaries for the China Inland Mission:

“There (at Brighton) the Lord conquered my unbelief, and I surrendered myself to God for this service. I told him that all responsibility as to the issues and consequences must rest with him; that as his servant it was mine to obey and to follow him.”

His apostolic vision was “to evangelize all China, to preach Christ to all its peoples by all and any means that come to hand.” He encouraged others to dream a dream so big that unless God intervenes, it will fail. Taylor loved to trust God for the seemingly impossible:

“There are three stages to every great work of God; first it is impossible, then it is difficult, then it is done.”

Sailing to China in 1866 with his first twenty-two CIM missionaries was a major ordeal. For fifteen days and nights, the stress of storm and tempest crashed upon their Lammermuir ship. Caught in one typhoon after another in the China Sea, their sails and masts were all gone. Yet Taylor stayed inexplicably calm. The sailors gave up hope, refusing to even try to save the ship. Taylor told the sailors that God would bring them through it, but they had to play their part. Returning to their duties, all survived without serious injury. A vessel, however, coming right after them lost 16 out of 22 crewmen.

In 1885, following Taylor’s second furlough, the Cambridge Seven responded to the missionary call to China, including CT Studd who later felt called to Africa. Over time, more than 800 missionaries joined Taylor serving in 300 different CIM mission stations and 125 schools. Today, 1,600 missionaries serve with CIM/OMF in East Asia.

The missionary life was often a lonely one. Taylor eagerly anticipated letters from home. When none arrived, he would often feel disappointment. As part of Taylor’s recruiting new missionaries, he invited them to carry their cross and be willing to lay down their life:

“If you want hard work and little appreciation; if you value God’s approval more than you fear man’s disapprobation; if you are prepared to take joyfully the soiling of your goods, and seal your testimony if necessary with your blood…”

Sacrifice and humility, like Jesus did, was the key for missionary breakthrough. Self-indulgence was the enemy. Taylor commented,

“China is not to be won for Christ by self-seeking, ease-loving men and women. Those not prepared for labour, self-denial, and many discouragements will be poor helpers in the work.”

Because Taylor and the CIM missionaries were on the frontlines, they were sometimes the target of violence during times of unrest. Even though Taylor vigorously opposed the opium trade, all western missionaries were falsely linked with the British pro-opium policy. The Duke of Somerset in 1868 urged in the House of Lords that all British missionaries should be recalled from China because they were not good for British business. In 1900, during the Boxer rebellion, there were 58 CIM missionaries and 21 of their children killed, more than any other mission agency. Taylor nearly died of grief, saying “”I cannot read, I cannot pray, I can scarcely think…but I can trust.”

Taylor was passionate about Christlikeness in the missionary adventure. Deeper surrender to God’s will brought greater missionary breakthrough: “The real secret of an unsatisfied life lies too often in an unsurrendered will.” Taylor discovered that in obedience to the Lord, the burden and responsibility rested with the Lord. He did not have to produce the results. His favourite missionary song became “Jesus, I am resting, in the joy of what Thou art.” Reflecting on his initial surrender,

“Well do I remember as in unreserved consecration I put myself, my life, my friends, my all upon the altar, the deep solemnity that came over my soul with assurance that my offering was accepted. The presence of God became unutterably real.”

One of the great joys of his life was in his marriage to Maria Dyer, a fellow missionary in China. Under pressure from her missionary mentor, she initially rejected Hudson’s marriage proposal. Six weeks after their wedding, Taylor wrote “Oh, to be married to the one you do love, and love most tenderly and devotedly, that is bliss beyond the power of words to express or imagination conceive.” He and Maria created a publication later called China’s Millions, which became a missionary catalyst for many. Maria passed away at 33, soon after their 5th son died of cholera. Hudson`s second wife, fellow missionary Jenny Faulding, was a great consolation to Hudson. Both wives shared Hudson`s deep love for China. Sadly, four of Hudson`s eight children died before the age of ten.

Hudson was sacrificially generous. In 1860, he wrote,

“If I had a thousand pounds, China should have it – if I had a thousand lives, China should have them. No! Not China, but Christ. Can we do too much for Him? Can we do enough for such a precious Saviour?”

Our prayer is that Hudson Taylor’s missionary example will inspire us to love the Chinese people with Christ’s sacrificial love.

Leave a Reply